“now it’s dark and i’m alone but i won’t be afraid”: the langley schools music project and educational play as catharsis

a forgotten 1970s school music project finds new life decades later, revealing how play, especially in children’s hands, can be a radical, cathartic, and deeply moving form of art.

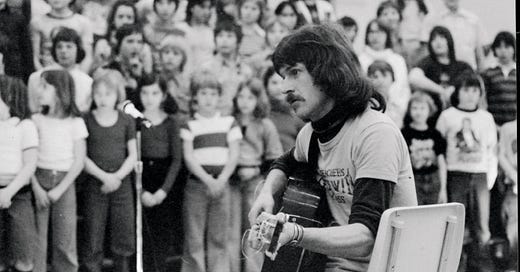

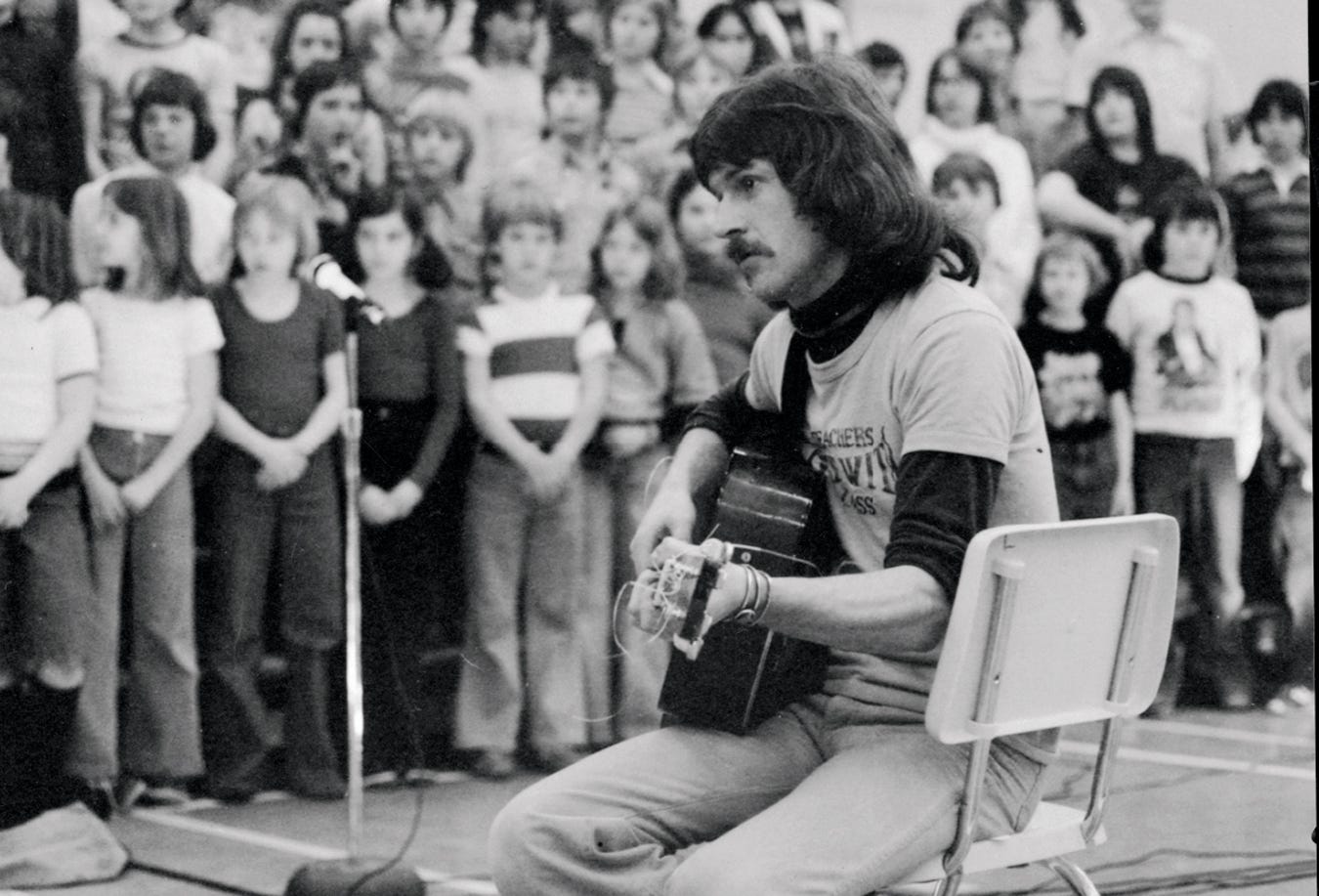

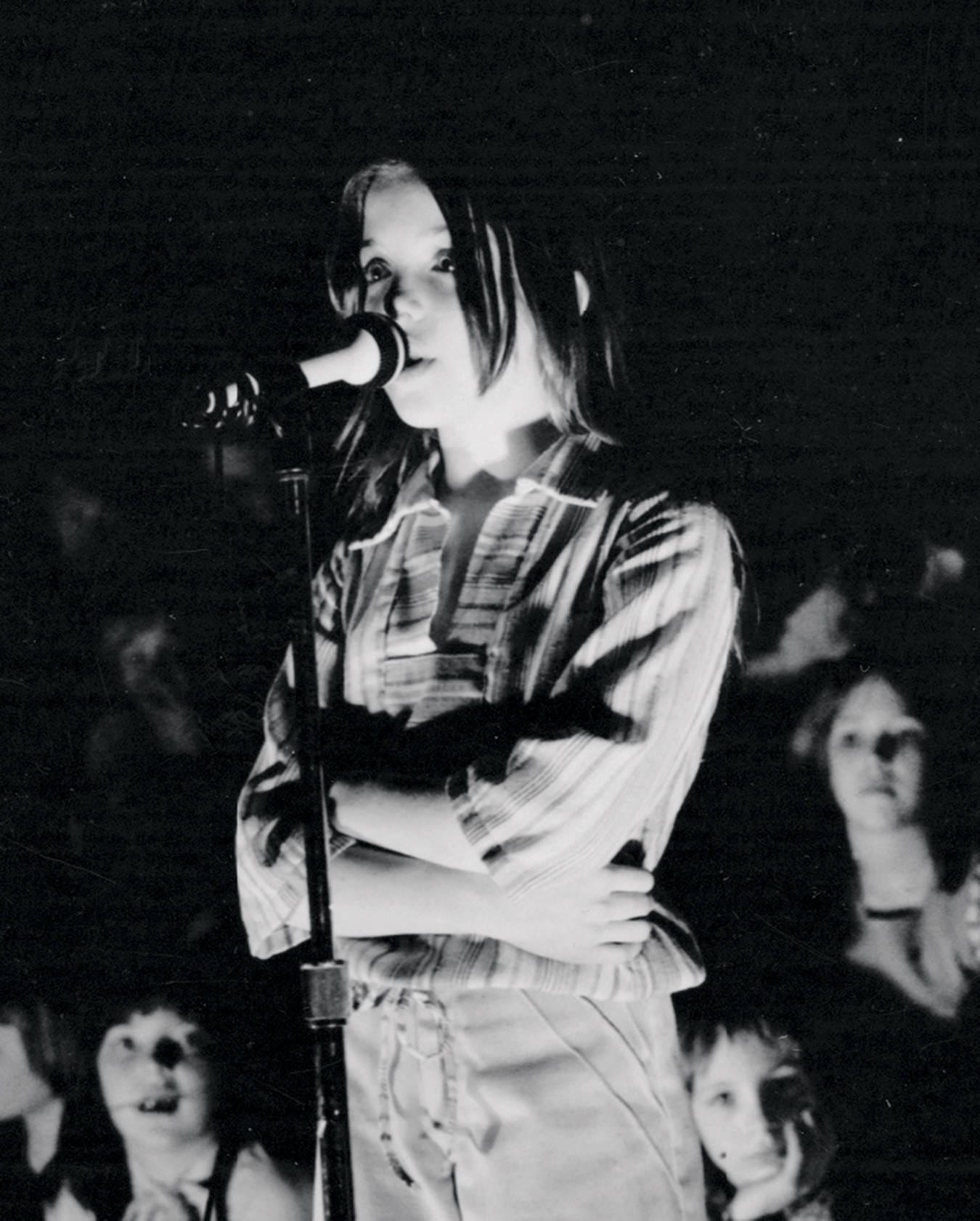

in 1976, hans fenger, a canadian music teacher and musician, began teaching pop covers to elementary school students across british columbia’s langley school district. kids between the ages of 9 and 12 learned everything from the beach boys’ “god only knows” and david bowie’s “space odyssey” to the eagles’ “desperado” and fleetwood mac’s “rhiannon.” after practicing the parts, which ranged from chorus to cymbals, drums, guitar, and other instruments available through music theorist carl orff’s schulwerk music teaching program, the kids were recorded performing the songs in echo-y school gyms. these recordings would result in two lps released in 1976 and 1977. and for two decades, that was the end of it. the langley schools music project pressings, of which there were supposedly around 300 copies, receded in closets and storage units, lost to the dustbin of the personal histories of the students who quickly became adults.

what we make as kids can be melancholic in this way. we’re always repressing the past to move forward. compound that with the oft-held belief that what we make as kids is inherently naive and therefore disposable, and the timeline of obsolescence only quickens.

thankfully, a different fate would eventually meet the langley schools music project. in 2000, a record collector came across fenger’s recordings and sent them to an outsider music aficionado. after trials and tribulations, the new jersey label bar/none records released the recordings as the double lp innocence & despair in 2001. from there, the project would gain a cult following. in a 2002 review for pitchfork, dominique leone perfectly articulated the odd aesthetic promise of innocence & despair, “the thing is, these people put so much joy and interest (trust me, having interested kids is never a given for teachers) into the proceedings, that they make this cd good by sheer force of will.”

what has long struck me about the will behind the langley schools music project is that it is less centered on power and more aimed at catharsis. after all, leone rightfully recognized the fact that these kids, especially in the airy piano solo “desperado” and the percussion-backed harmony of the already sad “space oddity,” more often than not produced emotions more “melancholic” than joyous.

that children can express themselves through music and art in such a way is not only indispensable to their healthy development, as individuals and communities, but also points to one of the more undervalued aspects of children’s supposedly naive form of making: the potential for surprise. through the element of surprise, projects made by kids like the langley schools music project, the oft-viral ps-22 chorus, or the early 2000s california tween girl band x-cetra offer a rebuttal to those binaries of teacher-student, expert-amateur, and knowledge-naivete often implicit in arts and music education—at the same time that they relied on working intergenerationally with adults in some fashion, be it to produce, mix and master, learn to read music, or even simply to distribute it.

of course, it didn’t hurt that the langley schools music project was intentionally approached with an alternative pedagogical practice. inspired by carl orff’s program, which emphasized learning through play rather than formal rigor, and having to contend with the under-resourced nature of the then-rural school district’s music program, fenger’s approach was experimental from the get-go. one could even call it radical, as stephen deusner does in stereogum: “fenger tailored the curriculum to speak to his students’ inner lives. instead of light fare, he understood that the kids were attracted to songs that addressed their darker fears.”

to reduce children’s play solely to the expression of joy is to limit play from the possibilities it creates. it also limits what their play can teach us as adults, teachers, and even patrons finding genius, or some lofty meaning in their work years later.

as i’ve been re-listening to innocence & despair recently, i’ve been reminded of the work of another person who, much like fenger, dedicated himself to the importance of play: allan kaprow. known best as a performance artist and founder of “environments,” a 1950s precursor to installation art, and the 1950–60s art world “happenings” craze, kaprow was never one for formalizing art. as a theorist, he could of course be highly verbose and academic (he was a full-time professor at the university of california san diego for nearly 20 years), but he never attempted to limit art to the rigidity of language. even in his theoretical writing, kaprow often argued for art free from many of the frivolities that come with growing up, like professionalizing language or subjecting play to process.

in his 1997 essay, “just doing,” kaprow recounts various ways that he “played” with friends, colleagues, family members, and strangers over the preceding decades. he would deliberately walk on a friend’s shadow on hikes, switching places as soon as the other’s shadow unexpectedly shifted direction. another time, he invited attendees at a conference to turn the light switch on and off as they wished, resulting in an over two-hour long experiment wherein academics playfully sat in silence and flicked the switch on a whim. boring as it may sound, this simple social experiment of sorts held a larger truth for kaprow, which was that play created the most experimental and interesting art.

in that same essay, where kaprow writes that “the art is the forgetting of art,” he advocates for play, as an open-ended act, as the path toward the purest form of expression. after all, when one plays rather than games, which kaprow characterizes as doing something with a predetermined objective to win, one also keeps the space for unexpected beauty open. playing can be scary as an adult, especially in the professional spheres of art and culture, where play is rarely rewarded in the moment and is only occasionally revered after the fact. but the risk of playing also offers something more timeless than the fleetingness of good reception: the potential for art to offer actual emotional reprieve.

in bleak times such as these, the cathartic promise of art is imperative. and catharsis doesn’t have to only produce joy, or hope, or defiance. sometimes, what’s first needed is a release of any sort, even if it’s melancholic. after all, the restorative work doesn’t truly begin until one is freed from the paralyzing numbness of trauma. in a time when the world of grown-ups rarely plays and rarely offers non-ironic or immediate paths to emotion, the artifacts of yesteryear, particularly those produced by children, offer us an alternative.

and as hundreds of thousands, including karen o and david bowie, have discovered in the years since the release of innocence & despair, the langley schools music project did just that. the songs might sound particularly emotional for a group of elementary school kids, but it is through experiencing sadness—and joy, excitement, and introspection—that they learn not to be scared. even when they harmonize on the last verse of the beach boys’ pensive “in my room,” the langley kids somehow lend things an air of hope: “now it’s dark and i’m alone but i won’t be afraid.”